Pinworms are uncomfortable for anyone, but for sensitive individuals they can be genuinely overwhelming. In my 15 years working with UK health and education teams, the toughest cases were never the “straightforward” infections – they were the children with sensory issues, adults with skin conditions, anxious parents, or people who’d had bad reactions to medicines in the past. What pinworm treatments do for sensitive individuals, when handled thoughtfully, is more than clear a parasite; they provide structure, predictability and a sense of safety in a situation that can easily feel out of control.

Why Sensitivity Changes The Treatment Equation

In theory, pinworm treatment is simple: take a short course of medicine, tighten hygiene for a couple of weeks, and move on. In practice, sensitivity complicates every step. A child with autism might find swallowing tablets or changing routines intensely stressful. Someone with eczema may flare up badly if they start showering more often or using new products. An adult who’s had past side‑effects from medication might quietly resist taking anything at all.

What I’ve learned is that you can’t treat “the pinworms” in isolation; you have to treat the person who happens to have pinworms. That means asking early: what has gone badly with medications or health routines before? Which parts of the usual advice are likely to trigger distress, anxiety or physical reactions? Once you know that, you can design a plan that genuinely fits, rather than forcing a sensitive individual through a textbook process that’s perfect on paper and miserable in reality.

Tailoring Medication Without Over‑Treating

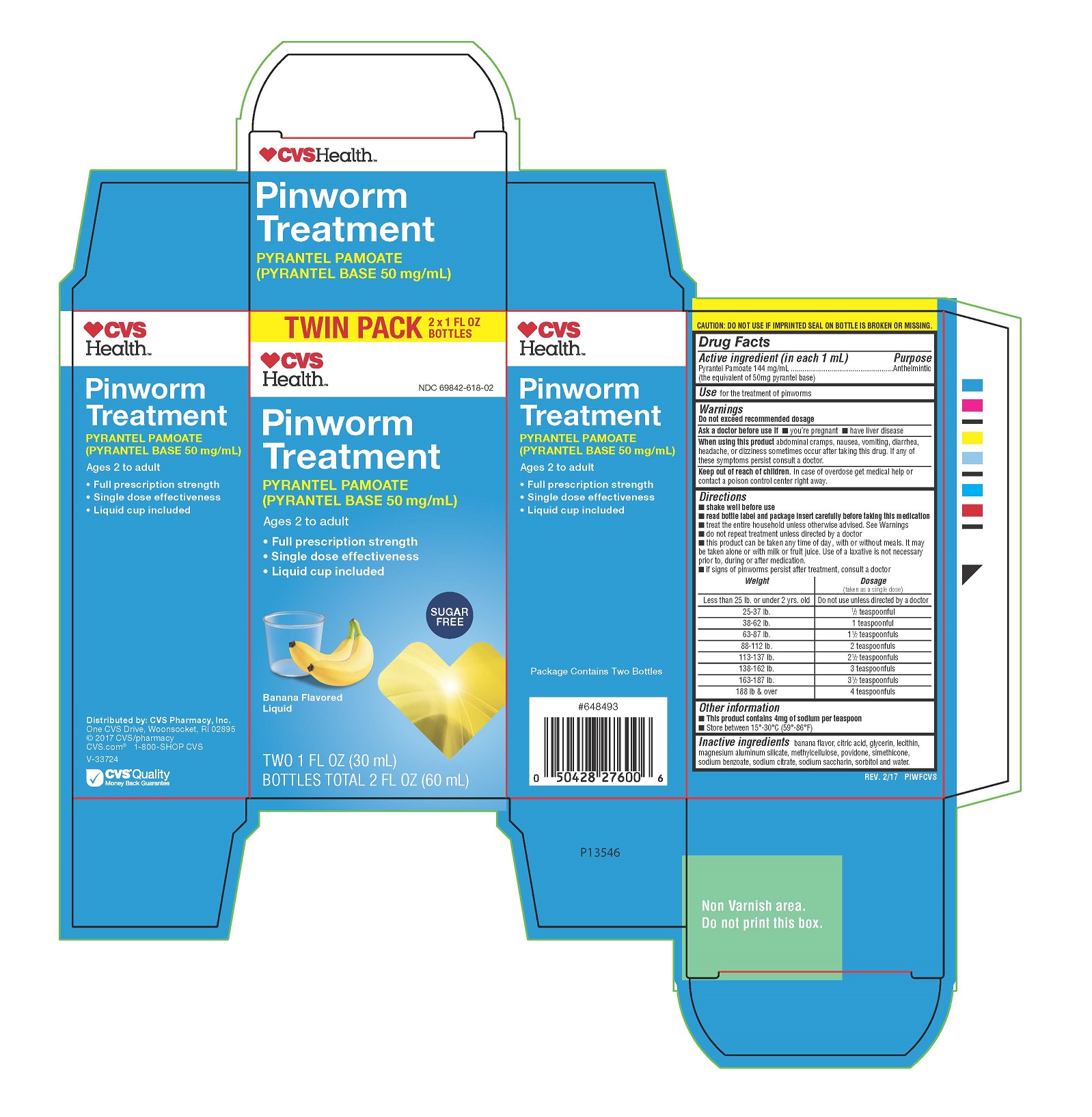

For sensitive people, the first fear is often the medicine. Parents ask, “Will this upset their stomach?” or “Is this safe with their other conditions?” Adults who’ve had bad experiences with drugs are wary of anything new. From a practical standpoint, the good news is that pinworm medicines are usually short‑course and low‑dose. The trick is not to add complexity for the sake of it.

I’ve seen well‑meaning relatives pile on unnecessary products – extra “detox” supplements, herbal capsules, multiple over‑the‑counter remedies on top of the prescribed medicine – and that’s where sensitive systems tend to protest. The calmer, safer approach is a single, agreed medicine at the right dose, plus careful observation. If there’s a known allergy or interaction risk, that conversation happens upfront with a clinician, not afterwards in A&E. Once the medical piece is set, you resist the urge to tinker. The 80/20 rule applies here: 20% of the treatment (the properly chosen medicine) does 80% of the worm‑clearing work. You don’t need to drown a sensitive body in extras.

Adjusting Hygiene And Cleaning For Skin And Sensory Issues

Hygiene advice – more showers, more handwashing, more cleaning – sounds harmless until you apply it to someone with sensory overload or fragile skin. A child who already hates water on their head, or an adult whose hands crack from frequent washing, will not magically tolerate a sudden spike in those routines. If you push too hard, they push back, and adherence collapses.

Here’s what works better. You keep the goals the same – remove eggs from skin and surfaces – but you adjust the method. For a child who can’t cope with full showers, a quick morning wash of the lower body might be acceptable, combined with clean underwear and pyjamas. For someone with eczema, you switch to fragrance‑free emollient washes and moisturise immediately after, rather than using whatever harsh soap happens to be in the dispenser. You focus handwashing on key moments (after the toilet, before food) and keep the water lukewarm with a gentle cleanser, instead of obsessively washing all day and shredding the skin barrier.

In terms of cleaning, you keep it targeted rather than aggressive. Hot‑washing underwear and bedding, wiping high‑touch surfaces once a day, and avoiding aerosol sprays around asthmatics or chemically sensitive people reduces eggs without triggering respiratory or skin reactions. It’s a measured response, not a chemical blitz.

Managing Anxiety And Loss Of Control

For many sensitive individuals, the worst part of pinworms isn’t the physical symptom, it’s the feeling that their own body or home is suddenly “contaminated.” I’ve seen highly capable adults spiral into obsessive cleaning, constant body‑checking, and online research at 3am, all because nobody framed the situation clearly at the start. Children pick up on this energy instantly and may develop their own fears about dirt, bathrooms or bedtime.

From a practical standpoint, the most helpful thing pinworm treatment can do in these cases is restore a sense of control. That starts with a clear, finite plan: here’s the medicine schedule, here’s the hygiene routine, here’s how long we expect things to take. You emphasise that this is a short‑term campaign, not a permanent state. You also normalise the infection – explaining that pinworms are common, not a sign of being “dirty” – to take the shame out of it.

For anxious personalities, having a single, trustworthy explainer to refer to is invaluable. Instead of bouncing between alarming forums, they can go back to a structured medical overview of pinworm infection – covering causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, prevention and complications – from a professional resource such as PrepLadder’s microbiology guide. That doesn’t replace a GP, but it stops the imagination filling gaps with worst‑case scenarios.

Supporting Neurodivergent People Through Change

Neurodivergent individuals, especially autistic children and adults with ADHD, often struggle with sudden shifts in routine and sensory load. Pinworm treatment touches multiple daily routines at once: medication times, washing, clothing changes, even how beds are made. If you change everything overnight with no warning or structure, you almost guarantee meltdowns or non‑compliance.

What I’ve seen work in UK families and schools is treating it like any other planned change. You explain what will happen, for how long, and why. You use visual schedules or social stories for children who respond well to them. You pair less‑liked tasks (a quick wash, a tablet) with something positive (a favourite story, a short video, a specific reward). You involve the person in choosing small aspects of the routine – which clean pyjamas to wear, which soap to use – so they feel some agency rather than being “done to.”

The reality is that the biology of pinworms doesn’t care about anyone’s neurotype, but the success of treatment absolutely does. If you respect how a sensitive brain and nervous system work, you can design a plan they’ll actually follow, rather than one you’ll spend two weeks fighting over.

Balancing Household Protection With Individual Limits

There’s always a tension between doing “everything possible” to protect the household and not overtaxing the most sensitive member. I’ve watched parents push one child well past their limits because they’re terrified of siblings getting infected, and I’ve seen the opposite – one person shielded so much that everyone else ends up under‑treated. Neither extreme is sustainable.

From a pragmatic business leader’s lens, you treat this like any risk‑management problem. You identify your constraints – the individual’s sensitivities, the physical space, the time available – and you ask, “Given these, what is the highest‑yield set of actions we can take?” That usually means prioritising: correct dosing for everyone, essential hygiene habits that the sensitive person can tolerate, and focused cleaning of the most likely transmission points.

It also means accepting that perfection is not required. You don’t need 24/7 glove use and hourly sheet‑changes to stop pinworms. You need enough well‑chosen actions, done consistently, that the parasite’s life cycle is broken. Sensitive individuals benefit enormously from hearing that message: “We’re going to do enough, not everything, and that’s okay.”

Using The Experience To Strengthen Future Resilience

Done badly, pinworm treatment can leave sensitive individuals more fearful of health issues and medical care. Done well, it can actually build resilience. I’ve seen anxious teens who, after getting through a clearly managed pinworm episode, were less terrified of future treatments because they’d experienced a finite, successful process. I’ve seen autistic children who, with the right supports, learned that they could survive a temporary change in routine and come out the other side.

The key is debriefing once the dust settles. You talk about what worked, what was too much, and what you’d do differently next time. You adjust notes in care plans or school records. You capture the “lessons learned” in the same way a good business would after a project. Over time, that knowledge means the next infection – whether pinworms again or something else – is handled with less stress and fewer missteps.

From a wider UK public‑health perspective, sensitive individuals are often the ones who suffer most when systems are blunt or inflexible. When you design pinworm treatments that respect sensitivity – minimal but effective medication, adapted hygiene, clear communication and real choice where possible – you’re not just clearing one parasite. You’re demonstrating that the system can be both competent and humane, and that’s the kind of public‑health culture that serves everyone well, whether they’re sensitive or not.